By Juan Fabbri

I explore the encounters between art and anthropology through a personal exercise: thinking and developing ideas through conceptual drawing. Drawing is an accessible tool — it only requires paper and pen — that, in addition to enabling creation and communication, opens paths for interpreting reality and for reinterpreting it.

In this exercise, I propose a constant back-and-forth between drawing and writing. My aim is to produce a text that allows us to think of anthropology as a profoundly creative discipline. The argument is that drawings can lead to other, new ideas just as text does in its own way. Ideas that are often questions about cultural reality, history, and life.

Conceptualismo del Sur is an artistic movement that draws from the influence of European conceptual art but from a Latin American perspective. Conceptual art is characterized by the dematerialization of the art object or images and the importance of the idea over technique; important precursors such as Duchamp and Kosuth allowed us to think about art from this other approach. In Latin America, Conceptualismo del Sur emerged as a way of working within conceptual art but epistemologically situated in the South. The work of the Uruguayan Luis Camnitzer was a starting point.

In Bolivia, Narda Alvarado, Santiago Contreras, the Mujeres Creando collective, Rodrigo Rada, Roberto Valcárcel, among several others, are part of an artistic movement that emphasises the importance of ideas and political stance over technique. Drawing does not seek to mimic reality in a realistic way, but rather to construct ideas.

Drawings, like words, can lead to new ideas. In this work, drawing is not just illustration but part of the research process, especially in interpreting the historical and social reality of Tiwanaku, with attention to power relations and my own perspective on them.

Bolivian Altiplano

Image 1. The altiplano between high mountains

My research takes place in the Bolivian altiplano, a vast plateau located at approximately 4,000 meters above sea level. This altiplano is framed by mountain ranges that contain snow-capped mountains reaching between 5,000 and more than 6,000 meters in height, such as Nevado Sajama (6,542 m), Illimani (6,438 m), and Huayna Potosí (6,088 m). The altiplano is an extensive line on the horizon.

Within the altiplano, I focused my research on Tiwanaku, Bolivia, which is located on the shores of Lake Titicaca — the highest navigable lake in the world.

Image 2. The altiplano

Image 3. The Altiplano and Lake Titicaca

Long History

Image 4. The archaeological site of Tiwanaku

Image 5. Camelids and Tiwanaku

In this area lived one of the most important pre-Hispanic cultures, known as Tiwanaku. In this territory, archaeological findings have determined that it was the center of the Tiwanaku culture. Among the remains that exist are stone stelae, ceramics, monumental architecture, and textiles dating from 500 BCE to 1200 CE.

In the archaeological material culture of Tiwanaku, we can see the importance of camelids, particularly llamas, for life in this ecosystem. Llamas provided wool, meat, were used as pack animals, and were also sacred animals that were part of rituals.

Today, at the archaeological site, there is an important monument called the Gate of the Sun. It is a kind of carved stone arch that symbolizes the belief in the sun as a god. This monument is one of the icons of Tiwanaku and is part of what is taught in schools about the past of Bolivian territory.

Currently, in Tiwanaku — particularly at the so-called Gate of the Sun — every June 21 the winter solstice celebration is held, called the Aymara New Year. Andrew Canessa (2012), “Tiwanaku and the Indigenous State” section) argues that in Bolivia a way emerged to (re)invent indigenous cultures, revisiting and taking an interest in the pre-Columbian past as a way of thinking about a non-colonial indigenous past, and also as a way of conceiving of the indigenous person in terms of citizenship. Canessa mentions how Evo Morales built the importance of Tiwanaku both by naming himself president of the country and by making his link with the indigenous — and therefore his link with the pre-Colonial era — visible, and also when he celebrated his first Aymara New Year as President. All the Aymara New Years in the following years were a way of reactivating the link with the indigenous, a link that was related to archaeology during the solstices of June 21. Revisiting the pre-Columbian era would be a way of decolonizing Bolivia, insofar as the references would cease to be those brought by colonization (such as those related to the Catholic religion) and instead other sacred, aesthetic, and political references related to the pre-Colonial era would be sought.

Colonization

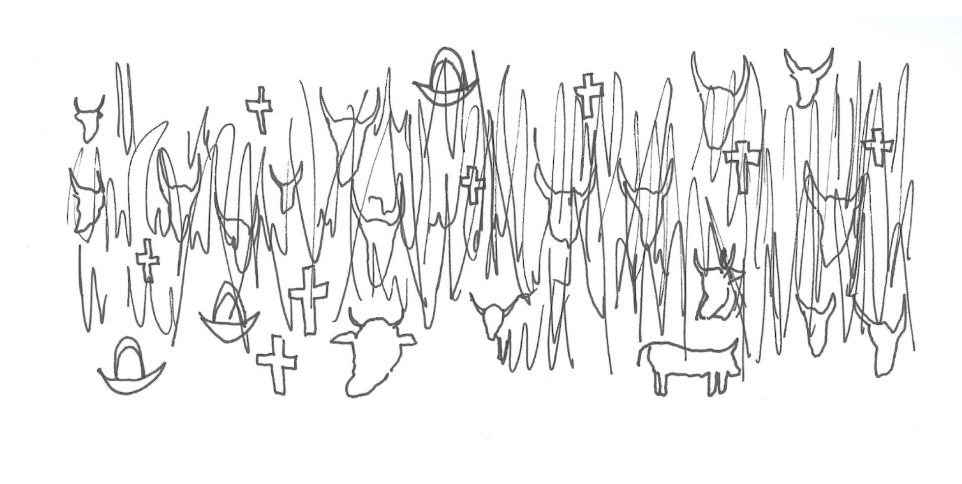

Image 6. Cross, colonial helmets, and cattle

Image 7. The altiplano in the colonial era

Colonization reached the Bolivian altiplano around 1535. The Spaniards arrived and imposed the Catholic religion; they brought bulls and cows mainly for plowing and agricultural work. In the years following the arrival of the Spaniards, control of the territory was exercised by them, and the indigenous peoples were in a constant situation of resistance and uprisings.

In 1825, independence from the Spanish crown was achieved in Bolivian territory; however, this did not mean the abolition of the semi-slavery system (is call pongueje) in which the indigenous people lived, which lasted until 1952. Only in 1953 did the Aymara people recover their lands, and they rebuilt their communities and ayllus.

The Latin American decolonial thought, and particularly that of Peruvian Aníbal Quijano (2014), considered that in Latin America there existed a colonial system related to the Spanish crown and the arrival of invaders from Europe to America, but that there also exists coloniality — that phenomenon of understanding that beyond the colonial system, colonial values and structures continued and are even present today. This is what we call coloniality. Colonialism imposed a Catholic religious system, established Spanish as the official language, and structured society through power relations linked to access to and control of land. Coloniality is the continuation of this system even though the Spanish crown is no longer present.

In my drawings, I propose the relationship between Catholic crosses, colonial helmets, and the arrival of animals such as cows and bulls as part of a system of imposition. The Catholic crosses represent religious imposition. The helmets represent military and administrative imposition. The cattle represent control of the land. Colonialism imposed a different way of understanding the world, which produced a social and cultural crisis for indigenous peoples.

In one of my conversations with an Aymara man while we were on the minibus, I mentioned that the landowners lost their land during the National Revolution. He, an Aymara man of about 45 years of age, said to me:

No [emphatically]. You’re wrong. They didn’t lose their land. That land never belonged to them. They invaded that land and used the whip to keep the people from rebelling for years. It’s as if we lost a war with Chile right now, and suddenly all these territories are Chilean. That’s how it was. But the land never belonged to them, so they haven’t lost anything.

During the hacienda era, in one of the dialogues, he tells me: What was produced was for the patrones (landowners). My great-grandfather told us that only one day out of the seven days of the week was what was produced used to support his own family. The rest was for the patrón (boss). From here (Tiwanaku) we carried the products, mainly potatoes, by donkey. We had to walk all day, and sometimes, if they were very heavy, we walked for two days. The donkeys had to carry the products on their backs. The bosses here had their jiliris who whipped the peasants to make them work. (Diary, March 2024)

If in my first drawings I understand the altiplano as an extensive line on the horizon, when I imagine colonization, I think of that line becoming chaotic, full of crises and tragedies, invasions of elements of domination that disrupted the territory.

Dairy Farming in the Bolivian Altiplano as a Development Project

Image 8. Coins and bills with cow hair

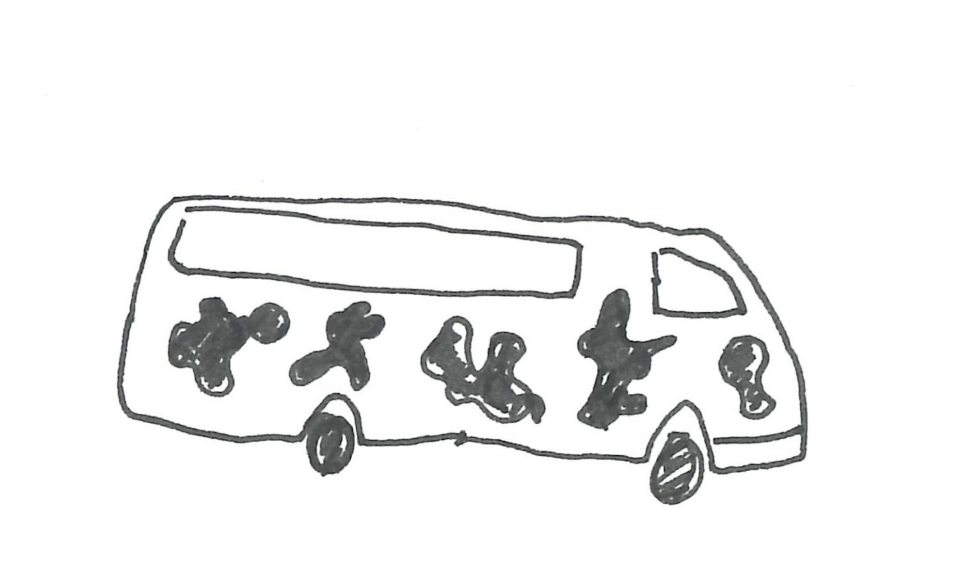

Image 9. Minibus and cows

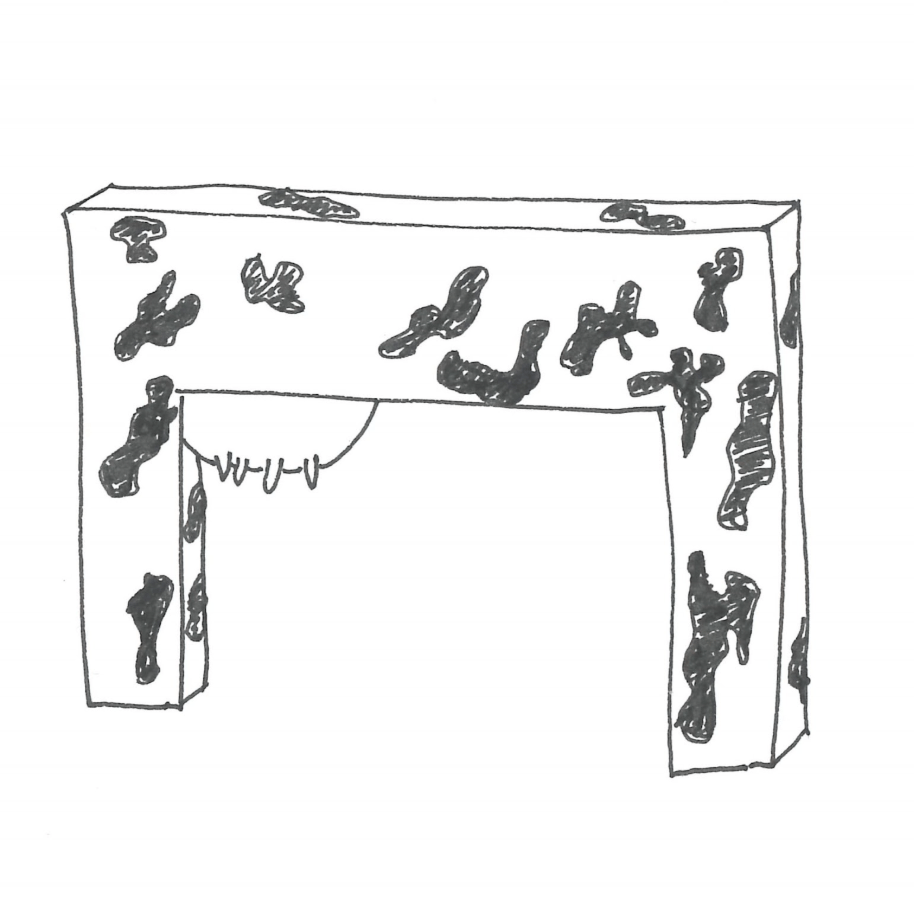

Image 10. Cultural material with cow hair

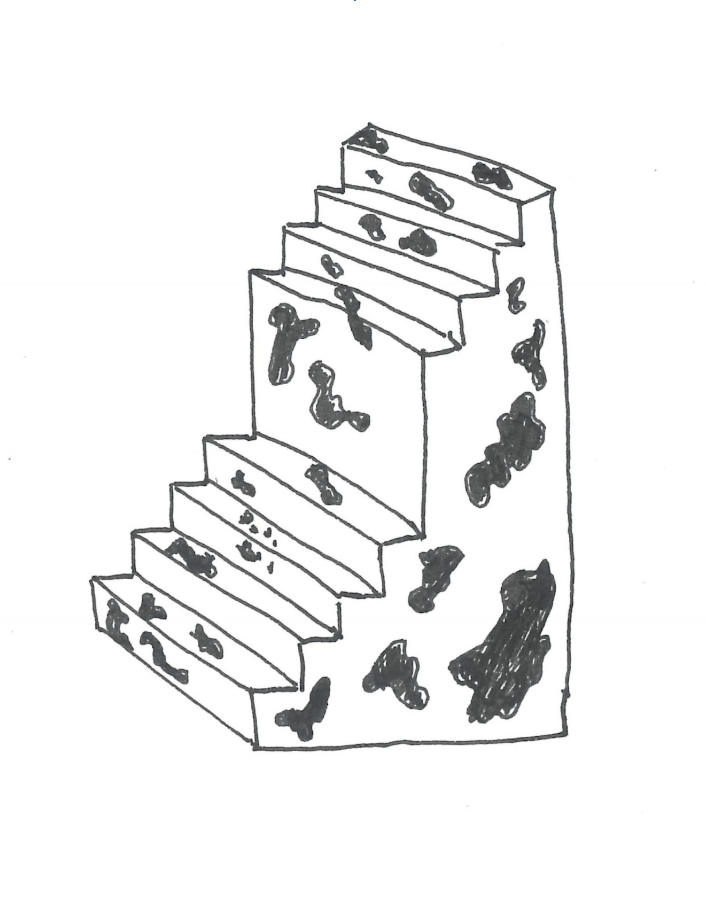

Image 11. Stairs as modernity and cows

I draw coins and bills with cow hairs. A minibus — common transportation in Tiwanaku — painted with the same aesthetic as a Holstein cow. Finally, a staircase that signifies the expectation of progress or development, but at the same time, is a staircase impossible to climb; that impossibility is part of the contradictions of modernity’s aspirations.

In the 1970s and 1980s, there was a process of migration from rural areas to the cities. It became increasingly difficult to live from peasant work. In that context, the Bolivian State — linked to Danish Cooperation and to the Catholic Church — promoted the arrival of dairy production to the area. It was then thought that the path toward development in the altiplano was dairy cows. The indigenous people initially resisted, but little by little they came to believe in the project, and milk became the main economic livelihood. They learned to raise cows. They replaced Spanish or Creole cows with Holstein or Brown Swiss cows, which they managed to adapt to 4,000 meters above sea level. Other animals, such as llamas and other camelids, are no longer seen in the area today.

Cows would then be related to progress — meaning access to money, modernity, or migrating to the city under better conditions. Dairy farming would be a form of progress and, at the same time, an alternative to migration.

In the Manifiesto de Tiwanaku, the indigenous people wrote:

We peasants want economic development, but based on our own values. We don’t want to lose our noble ancestral virtues for the sake of pseudo-development. We reject this false development that is imported from outside because it is fictitious and does not respect our deep-rooted values. We want outdated paternalism to be overcome and for us to no longer be considered second-class citizens. We are foreigners in our own country.

Talking with Bernardina Laura in my fieldwork, she mentioned that she was the one who organized the animal care course. She told me that back in the 1980s, PIL (one of the largest dairy companies in the country) had already approached them to buy milk from the region. However, at that time, very little was sold, and almost everyone was skeptical about improving the animals and feeding them alfalfa. There was no surplus alfalfa. However, the priest recommended it to them, even during Mass, and spoke to them about the importance of planting alfalfa for their animals. According to Bernardina, little by little, people began to plant alfalfa.

“At first, the cows’ bellies swelled from eating alfalfa and they died, and we lost our capital.”

Bernardina would mention:

But little by little, thanks to the work of the UAC and the support of some NGOs, we learned that the cow’s diet had to be controlled — that is, she could not eat alfalfa without restriction but had to eat measured amounts. Once we learned how to feed the cows, they stopped dying.

In another conversation, a young man told me that cows’ bellies swell when they eat wet alfalfa. That happens at the beginning of the rainy season, in November. He told me this is the most dangerous time for cows because they eat and cannot stop eating. The problem is that if they eat alfalfa that is wet because it has rained a little, the alfalfa heats up inside their stomachs, causing gas and swelling. At that point, you have to pierce their stomachs with a long nail to release the gas. If you do it in time, the cow will survive, but if you don’t, the cow will lie down and there will be no way to get it back on its feet. The cow lies down, and there is no way to make it stand up again. Then the cow dies.

Another danger is that you pierce it but make a mistake because it is difficult to find exactly where you have to pierce to release the gas. If you make a mistake, you can also kill the cow. On the other hand, it is not possible to call the vet because you have to react quickly; the cow cannot wait, or it will die. Once it lies down on the ground, even if it is alive, it will not get up again, which means it will die. The bad thing is that the meat is no longer suitable for sale. Once it dies in this way, the meat is tough, so it is no longer fit for eating. We can only bury it.

Dairy Farming Today as a Decolonizing Project

Image 12. Gate of the Sun turned into a monument to dairy farming

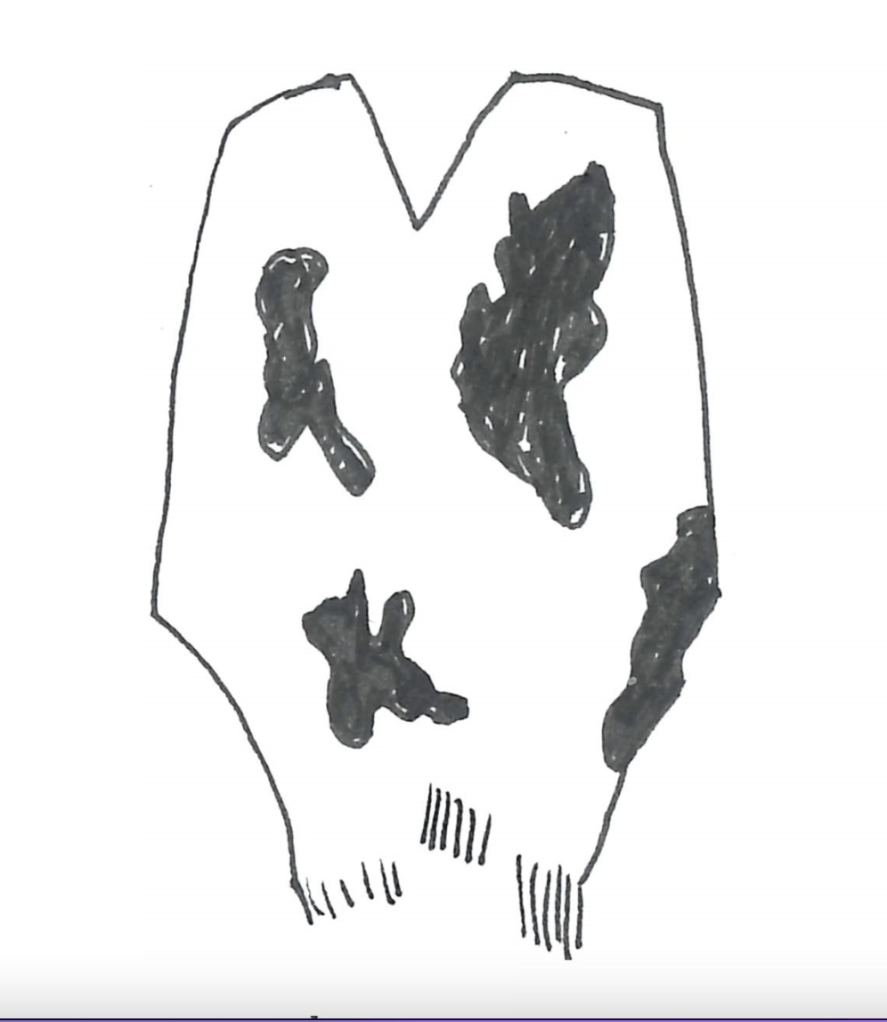

Image 13. Aymara poncho with cow aesthetic

Image 14. Indigenous clothing with cow and dairy farming aesthetics

I draw a Gate of the Sun that would, in fact, be a new monument to dairy farming. I draw material culture such as pre-Columbian ceramics intervened with cow hair and, inside, carrying milk, and I imagine, while drawing, the indigenous people with their traditional clothing — ponchos, hats, polleras — but using motifs dedicated to cows.

Then, I ask myself if dairy farming and cows can be a decolonizing project in the Bolivian altiplano. What would this mean? To imagine the possibility that the indigenous people could appropriate dairy work to sustain their economy, but also incorporate cows into their ontology — that is, into their own way of understanding the world.

It is then that an externally imposed development project, which is also part of a long colonial tradition in the area, can be rethought from decolonial logics. It is possible to imagine cows as a project that reduces the economic inequalities between peasant work and that of the cities.

These drawings are only a fiction of what Aymara culture could be, with its logics, aesthetics, and ways of understanding the world, where the presence of dairy farming and cows becomes an economic alternative and the possibility of maintaining their economic activity in the countryside — making migration a decision, not a necessity due to the lack of alternatives in rural areas. Thus, decolonizing does not mean rejecting everything that comes from other cultures or territories, but rather the possibility of incorporating it into one’s own cultural logics. That is, instead of generating cultural alienation, achieving that the other elements are transformed according to indigenous logics.

Conclusions

Draw, draw or draw. An exercise to trace reality, but also to imagine it. To think of utopias for the future. I consider anthropology to be a radical discipline for dreaming of a more diverse and equal world. It is a science that, beyond recording reality, also allows itself to dream and propose changes. On this horizon, drawing is also a way of imagining those changes.

My fiction of cows as a decolonizing project also enters into crisis when I think about the reality that the price of milk is regulated by large capitalist companies; the relationship between dairy farming and its consumers is mediated by transnational companies that reproduce inequality. The peasantry has its dreams and its ontologies, which I doubt the capitalist system can accommodate.

With these drawings I am accumulating, I hope to be able to dialogue with the field and continue getting to know reality in order to imagine it again. Sharing images in the field is more feasible than sharing texts. Images are excuses to keep the dialogue going.

References

Artishock. 2016. Fin de partida. Duchamp, el ajedrez y las vanguardias. Chile. Publicado el 22 de noviembre de 2016. Link: https://artishockrevista.com/2017/06/29/pablo-helguera-no-me-interesa-arte-artesania/

Cabanne, Pierre. 1972. Conversaciones con Marcel Duchamp. Barcelona: Anagrama.

Kosuth, Joseph. 2014. Escritos (1966-2016). Metales Pesados: Chile.

Camnitzer, Luis. 2009. Didáctica de la liberación: arte conceptualista latinoamericano. CENDEAC.

Canessa, Andrew. 2012. «De la arqueología a la autonomía», Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos [Online], Questões do tempo presente, posto online no dia 14 dezembro 2012, consultado o 23 maio 2025. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/nuevomundo/64577; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/nuevomundo.64577

Ponce Sanginés, Carlos. 1995. Tiwanaku, 200 años de investigaciones arqueológicas. Producciones CIMA. La Paz, Bolivia.

Sagárnaga, Jédu. 2007. Investigaciones arqueológicas en Pariti (Bolivia). Anales del Museo de América Núm. 15. España.

Quijano, Aníbal. 2014. Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y América Latina. En: Cuestiones y horizontes: de la dependencia histórico-estructural a la

About the author

My name is Juan Fabbri. I am Bolivian and Italian. Currently a PhD student in Cultural Anthropology at Uppsala University.

I completed my BA in Anthropology at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés in Bolivia, where I am now a teacher and researcher at the Anthropology Research Institute. I hold a Master’s degree in Visual Anthropology from the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences in Ecuador. I also have a background in the visual arts: I was the curator of the Bolivian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, as well as curator and chief of the National Museum of Art of Bolivia.

Email: juan.fabbri.zeballos@antro.uu.se

Lämna en kommentar